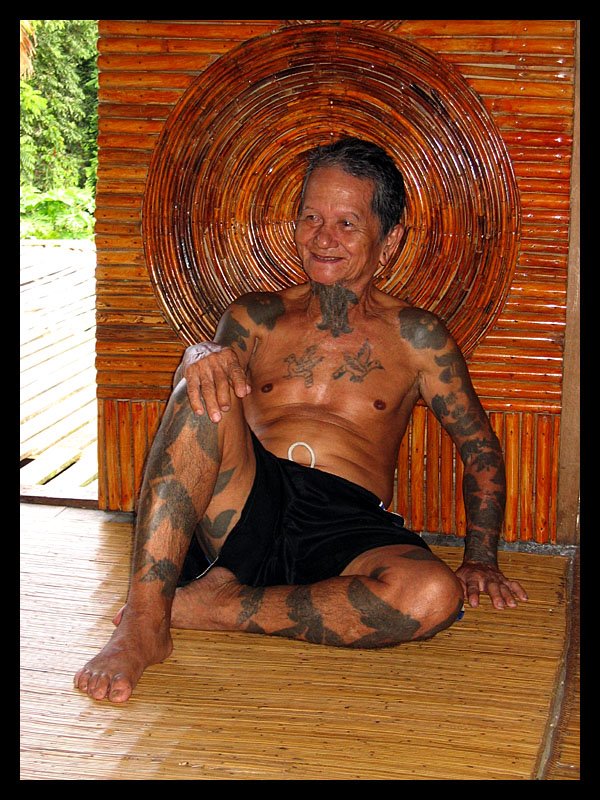

WOW !! TATTO TRADISONAL SUKU DAYAK.. NGERI BANGET..!!!

Painted Past: Borneo's Traditional Tattoos

For Borneo's Dayak peoples, spirits embody everything: animals, plants, and

humans, Krutak explained. Many groups have drawn on this power by using images

from nature in their tattoos, creating a composite of floral motifs using

plants with curative or protective powers and powerful animal images.

Tattoos

are created by artists who consult spirit guides to reveal a design. Among

Borneo's Kayan people, women are the artists, a hereditary position passed from

mother to daughter. Among the Iban, the largest and most feared indigenous

group in Borneo, men apply the tattoos.

These

tattoos are blue-black, made of soot or powdered charcoal, substances thought

to ward off malevolent spirits. Some groups spike their pigment with charms—a

ground-up piece of a meteorite or shard of animal bone—to make their tattoos

even more powerful.

For the

outline, the artist attaches up to five bamboo splinters or European needles to

a stick. After dipping them in pigment, he or she taps them into the skin with

a mallet. Solid areas are filled in with a circular configuration of 15 to 20

needles.

Ritual

Tattooing

Traditionally,

Dayak tattooing was performed in a sacred ritual among gathered tribe members.

Among the Ngaju Dayak, Krutak said, the tattoo artist began with a sacrifice to

ancestor spirits, killing a chicken or other fowl and spilling its blood.

After a

period of chanting, the artist started an extremely painful tattooing process

that often lasted six or eight hours. Some tattoos were applied over many

weeks.

For

coming-of-age tattoo rituals, the village men dressed in bark-cloth. This

cloth, made from the paper mulberry tree, also draped corpses and was worn by

widows.

Tattooing,

like other initiation rites, symbolized both a passing away and a new

beginning, a death and a life.

Head-hunting

Tattoos

One Dayak

group, the Iban, believe that the soul inhabits the head. Therefore, taking the

head of one's enemy gives you their soul. Taking the head also conferred your

victim's status, skill and power, which helped ensure farming success and

fertility among the tribe.

Upon

return from a successful head-hunting raid, participants were promptly

recognized with tattoos inked on their fingers, usually images of anthropomorphic

animals.

Head-hunting

was made illegal over a century ago—but even today, an occasional head is still

taken.

Tattooed

Women

In past

times, just as Iban men were tattooed to recognize their prowess in hunting or

warfare, Iban women were adorned for accomplishments in weaving, dancing, or

singing. Adolescent Kayan girls were tattooed at puberty to render status as an

adult, to attract men, and to provide protection against evil spirits.

As they

grew older, women were often covered by a weave of inked images spreading

around their legs, across the tops of their feet, forearms, and fingers.

But only

very wealthy Kayan women sported these intricate tattoos, Krutak

said—"only aristocracy who could pay with a sword, a gong, pigs, or old

trading beads." Only aristocratic women were allowed to use particular

designs, because only these women were powerful enough to resist any negative

magic associated with the designs themselves, he said. Slaves were forbidden to

tattoo.

Marking

Perfection

Tattooing

was done in stages over many years and was governed by various taboos. Once a

Ngaju man had acquired some wealth and reputation, his shoulders were adorned

with a star and his arms decorated with rooster wings and plant patterns.

"But

later in life, perhaps at the age of 40, only 'perfect' men would be allowed to

receive the complete form of Ngaju tattoo," Krutak said. These were men

who had distinguished themselves by living their lives according to ceremonial

law, participating in head-hunting expeditions and the offering of a human

sacrifice—and who had acquired wealth.

This

"complete" tattoo was applied over many days. The man's arms were

covered with images of areca palm fronds that were said to protect him from

malevolent jungle spirits. Then his torso was tattooed with a design of the

Tree of Life, an everlasting symbol of strength and divinity that protected him

from his flesh-and-blood enemies. He was then considered godlike, perfect and

sacred, and it was believed that in the next world he would receive a golden

body.

Among the

Iban, the chests and backs of older, venerated warriors were completely

decorated with a collage of powerful images. The hornbill was a favored motif

because the bird was seen as a messenger of the war god Lang and also marked rank

and prestige. Other favorites were the scorpion and the water serpent, which

protected the wearer from evil spirits lurking in the jungle.

But in

Borneo, and among many other indigenous groups around the globe, this practice

is fading. "Many traditional forms of tattooing are dying out," Keane

said.

source

0 Response to "WOW !! TATTO TRADISONAL SUKU DAYAK.. NGERI BANGET..!!!"

Post a Comment